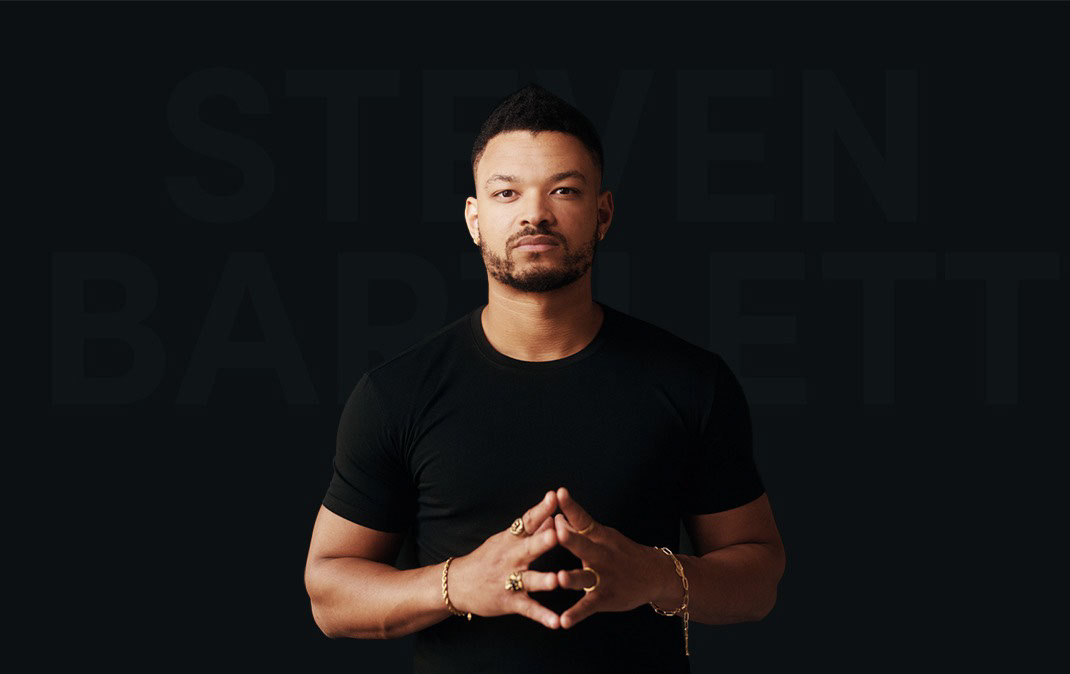

Steven Bartlett: Inside the diary of a CEO

Want to know the secret to success in business?

Well, according to one multimillion dollar entrepreneur it could just lie in your mental outlook – in optimism – rather than in academic success.

Steven Bartlett, the host of one of the biggest podcasts in Europe ‘the Diary of a CEO’ and the youngest ever dragon on BBC’s hit show Dragon’s Den, flew to the UAE to share his story with the Sharjah Entrepreneurship Festival.

During an inspiring and wide-ranging conversation on stage with moderator Sally Mousa, the 29-year-old author, investor and speaking, told the audience how his early years had shaped his ambitions, both from his upbringing to his humble start in adult life as a university drop out stealing food and mired in debt.

Steven Bartlett’s Bio:

Steven Bartlett is the 29-year-old founder of the social media marketing agency Social Chain. From a bedroom in Manchester, this university drop-out built what would become one of the world’s most influential social media companies when he was just 21 years old, before taking his company public at 27 years old with a current market valuation of over $600M.

Steven Bartlett is a speaker, investor, author, content creator and the host of one of Europe’s biggest podcasts, ‘The Diary of a CEO’. In 2021 Steven released his debut book ‘Happy Sexy Millionaire’ which was a Sunday Times best seller.

He’s also invested in, and taken a role as an advisor in Atai life sciences – a biotech company working to cure mental health disorders. Other investments focus on blockchain technologies, biotech, space, Web 3 and social media.

Recently, Steven has invested in two new businesses, Flight Story & Third Web. At just 29 years old, he is widely considered one of Europe’s most talented and accomplished young entrepreneurs and philosophical thinkers.

Steven joined Dragon’s Den from Series 19 in January 2022, as the youngest ever Dragon in the Show’s history.

Dive into part one of the Q&A on stage at the Sharjah Entrepreneurship Festival below.

Steven Bartlett’s beginnings

Sally Mousa:

So talk to us about how your experience growing up translates into who you are right here today?

Steven Bartlett:

Yes, so I was born in Africa. I was born in Botswana, and I moved to the UK when I was a baby. My mother is Nigerian. My dad is English. Still to this day, my mother can’t read and write.

So she she did a phenomenal job raising four kids in Plymouth pretty much on her own. We moved to Plymouth in the southwest of England, where I was the only black kids other than my siblings that I knew. We were in a school of about 1,500 children and we were the only black family.

We were also the only family that didn’t appear to have any money at all. So, we were the by far the poorest family and this is all really important context because those early years before you’re 10 years old, they end up shaping you in ways that end up playing out in your adult life, and that certainly was the case for me.

I always believe that the thing that invalidates us when we’re young ends up being the thing that we seek most validation from when we’re older. For me, I wanted more than anything that I knew, to be enough. I wanted to fit in, I wanted to have the nice shoes, the nice house all of those things.

Another real force behind me was a huge sense of independence. My mum started this corner shop and she got so busy preoccupied running that corner shop she stopped coming home. I’m the youngest of four, that’s the other important piece of context, sometimes the youngest child gets treated like your older children, I think my parents thought that they had already parented us enough. So the real force there was because my mum was so absent, and because I wanted so many things, I learned a very important lesson at that young age that anything that I’m going to have is going to be a direct consequence of my behavior. That’s where I think much of my entrepreneurship in hindsight comes from, it’s from the 14-year-old selling things, it’s starting to do things because I was insecure, because I was full of shame, so that I can buy the stuff that my friends had.

If you start running those experiments at 14 years old, by the age of 18,19 20, you’ve built up so much evidence within yourself about what you can do, that you can have an idea and you can make it a reality.

I think that’s much of the reason why I’ve managed to build businesses achieve so much at a young age. That really is the key to confidence, it’s all evidence, it all evidence you do or don’t if have. A lot of people in this room might think confidence is a choice you make. I don’t think you choose any of your beliefs. Sometimes the evidence is incorrect, but it’s all based on evidence. And the reason why I did come to know this is because at a very young age I got the evidence that when I have an idea it’s possible to make it happen.

Steven Bartlett’s secret of success

Sally Mousa:

So, at age 18 you were videoing yourself saying that this was for a documentary when you were rich and famous. Where did that stable belief come from that this was really going to happen?

Steven Bartlett:

I had no evidence to tell me in my life that I couldn’t do things. When I think about my academic performance in school, I got kicked out of school. I lasted one day at university before I dropped out. I can’t do maths, I can’t spell. If you look at any of the subjects I did at school, other than maybe business or psychology, I was a dreadful student.

I was trying to add it up the other day, Social Chain’s valuation went up to about $700 million, my new company Third Web was just raised investment from Shopify and Coinbase valued about $200 million, my marketing group in the UK is worth about $50 million, so it’s about a $1 billion of equity value I’ve created in the last 10 years, and I’m not good at finance, I’m not good at the business stuff.

And it’s funny because I sat with Richard Branson two weeks ago when he came on my podcast, and I found it really fascinating that Richard Branson didn’t know the difference between net profit and gross profit until he was 50 years old. Then someone pulled him out of the room, drew a picture of an ocean and put a net in the ocean and said ‘Richard all the fish in the net that’s your net profit. All the rest is your gross’. He was 50 years old and a multi-billionaire, and he’s also dyslexic.

I think that’s really empowering because we tend to think that really successful businesspeople are phenomenal operators, are phenomenal at maths and phenomenal at processes and all these things, and financing. No, it’s nonsense.

From my experience, the best entrepreneurs realise that they’re very good at very little, that they become extraordinary delegators and they triple down on the thing that they are uniquely good at. And, for me in my businesses, I’m good at very little, but I spent so long focusing on that thing that I’m really good at that I don’t think there’s anyone better at it than me.

When I look back at my diary when I dropped out of university, called my mum and said ‘I’m dropping out of university’ she said ‘if you drop out of university I’ll never speak to you again’ – she was telling the truth.

I moved to this really rough area where I was at the time, I was stealing food to feed myself, and I started recording a diary and on the first page of the diary, I wrote that a TV production company had asked me to record this diary because they wanted to make a documentary about me. That’s not true. I lied to my diary and I still to this day has no idea why. I then started videotaping my despair. I’d open my fridge and go ‘oh look nothing’, and I’d go through my bailiff letters and all the debt I was in and go ‘look, I’m really in a terrible situation’, and I was videotaping it all. And the reason I tell you this is because it’s the clearest indication of my perspective.

That moment of my life was a steppingstone, it wasn’t my destination. There was zero percent of me that thought that was my destination, this was just this really exciting story that I was going to tell one day. The reason why I said I wasn’t good at school and I didn’t have great academic performance is to highlight the one thing that I clearly did have which was a ton of self-belief. And I remember saying back then, even when I was like, 18, 19, 20, if you told me to go to the moon next week, my orientation was ‘there is a way to make that happen’.

That was my bias, they actually call it an ‘optimism bias’. I was always optimistic. I always thought there was a way to make the things I envisage happen. It’s self-fulfilling, it’s also self-fulfilling the other way. This week I sat with an expert on optimism on my podcast, and it’s interesting, because at 14 I try to do things and I do them with an optimistic attitude, and they do well, which reinforces that I can do things I try and do more things. Because I’m optimistic and I have the evidence that the previous experiments have gone well, I show more positively and it is self-fulfilling.

We’ve seen how optimism is self-fulfilling, the same applies the other way down. You can spiral down in your pessimism cycle, where you try something, you try it half-heartedly because you’re lacking in confidence. It doesn’t go well, it knocks your confidence and then you try less things, but even the things you do try you try them in a more fearful way so they go worse, and your confidence can spiral down.